Ironbound: A Comprehensive Guide to Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload Management

Introduction: Understanding Hemochromatosis and Iron Overload

Hemochromatosis is a genetic condition characterized by the body’s inability to regulate iron absorption properly, leading to excessive iron accumulation in various organs. Unlike most people, whose iron absorption is precisely controlled, individuals with hemochromatosis absorb more iron than necessary. This results in iron overload, which, if untreated, can lead to severe organ damage, particularly affecting the liver, heart, and pancreas.

The condition is primarily linked to mutations in the HFE gene, notably the C282Y and H63D variants. These mutations interfere with the hormone hepcidin, which is essential for iron regulation. As a result, iron continues to accumulate unchecked, creating toxic levels that cause significant health issues.

Often referred to as a “silent killer,” hemochromatosis can take years to present symptoms, and by then, irreversible damage may have occurred. However, with early diagnosis and appropriate management, individuals with hemochromatosis can maintain their health and quality of life effectively.

The Genetics of Hemochromatosis: Why Iron Accumulates

The Role of the HFE Gene and Hepcidin

The HFE gene on chromosome 6 plays a crucial role in iron regulation by influencing the production of hepcidin—the liver-produced hormone that regulates iron absorption from the diet. Hepcidin acts as a key iron regulator, signaling the intestines to adjust iron absorption to meet the body’s needs.

When the HFE gene mutates—specifically in the C282Y or H63D variants—it disrupts normal hepcidin production. The body fails to regulate iron absorption properly, and the intestines continue to absorb more iron than needed. Over time, this leads to iron overload, particularly in critical organs such as the liver, heart, and pancreas.

Common Genetic Mutations: C282Y and H63D

The C282Y mutation is the most significant genetic variant linked to hereditary hemochromatosis. Individuals who inherit two copies of this mutation are at high risk of developing iron overload, although not all of them will experience symptoms. This phenomenon, known as incomplete penetrance, indicates that other genetic or environmental factors might influence whether symptoms manifest.

The H63D mutation also contributes to hemochromatosis, especially in individuals who inherit one copy each of C282Y and H63D. These compound heterozygotes may develop iron overload, though it tends to be less severe compared to those with two C282Y mutations.

Inheritance Patterns: Autosomal Recessive Disorder

Hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder, meaning an individual must inherit two mutated copies of the gene—one from each parent—to be at significant risk of developing iron overload. Those with only one mutated gene are known as carriers and generally do not develop symptoms but can pass the gene to their children. Genetic counseling is often recommended for families affected by hemochromatosis to assess the risk for current and future generations.

Types of Hemochromatosis: Different Forms of Iron Overload

Hereditary Hemochromatosis (Classic Type I)

Hereditary hemochromatosis is the most common form of the condition, often found in individuals of European descent. It typically results from mutations in the HFE gene, most notably the C282Y variant, and presents in adulthood.

Juvenile Hemochromatosis (Type II)

Juvenile hemochromatosis is a rare, severe form of iron overload that appears early in life, often during adolescence or early adulthood. It is linked to mutations in the hemojuvelin (HJV) or hepcidin (HAMP) genes and can lead to complications like heart disease or endocrine issues at a young age.

Neonatal Hemochromatosis

Neonatal hemochromatosis is a rare condition causing severe iron accumulation in the liver during fetal development. Unlike other types of hemochromatosis, it is thought to have an autoimmune component rather than a purely genetic basis. Babies born with this condition often suffer from liver failure and require urgent medical intervention.

Secondary Hemochromatosis

Secondary hemochromatosis, or acquired iron overload, results from non-genetic causes, such as chronic anemia, alcoholic liver disease, or frequent blood transfusions. This type of iron overload is common among patients with thalassemia or other conditions requiring repeated transfusions.

Symptoms of Hemochromatosis: How Iron Overload Manifests

Chronic Fatigue and Joint Pain

One of the most common initial symptoms of hemochromatosis is chronic fatigue, which can be severe. It is often accompanied by joint pain, particularly in the knuckles. Joint pain is sometimes referred to as the “iron fist” symptom, especially when it affects the knuckles of the index and middle fingers.

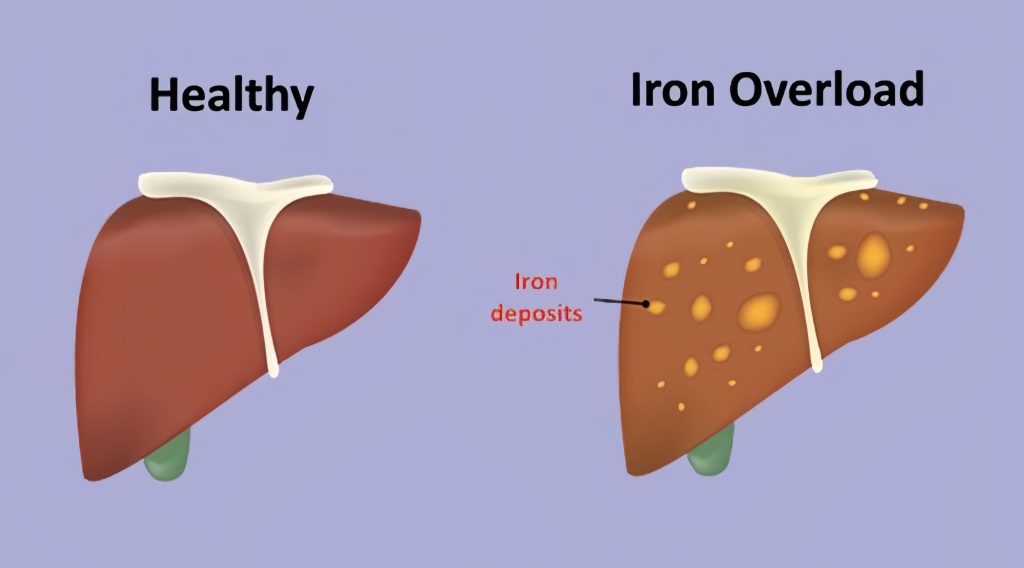

Abdominal Pain and Liver Dysfunction

Iron overload leads to hepatomegaly (an enlarged liver) and associated abdominal pain. Over time, excessive iron in the liver can cause liver fibrosis or cirrhosis, significantly increasing the risk of liver cancer.

Diabetes Mellitus

Excess iron in the pancreas can impair insulin production, resulting in diabetes mellitus—often called “bronze diabetes” due to the skin discoloration seen in advanced cases of iron overload.

Cardiac Complications

When iron accumulates in the heart, it can lead to cardiomyopathy, impairing the heart’s ability to pump effectively. This can cause heart failure and arrhythmias. Early diagnosis is vital to prevent lasting heart damage.

Skin Discoloration

Excess iron deposits in the skin lead to a bronze or grayish tint, often referred to as “bronzing.” This skin discoloration is one of the visible indicators of advanced hemochromatosis and iron overload.

Reproductive Issues

Iron overload affects hormone production, leading to hypogonadism. Men may experience impotence, decreased libido, and testicular atrophy, while women often face early menopause and menstrual irregularities.

Gender Differences in Symptom Onset

Symptoms generally present earlier in men due to the absence of menstruation, which naturally lowers iron levels in women. Women tend to show symptoms after menopause, when iron loss ceases, leading to an increased risk of iron overload.

Risk Factors for Hemochromatosis: Who is Most Vulnerable?

Genetic Predisposition

Having two mutated copies of the HFE gene—particularly the C282Y variant—places individuals at the highest risk for developing hereditary hemochromatosis.

Family History

A family history of hemochromatosis significantly increases the risk of developing the condition. Family screening is often recommended for early identification and management.

Ethnic Background

Hemochromatosis is most prevalent among individuals of Northern European descent, particularly those of Celtic origin. It is far less common among individuals of Black, Hispanic, or Asian ancestry.

Gender

Men are generally more likely to develop hemochromatosis at an earlier age compared to women. Due to iron loss through menstruation and pregnancy, women are often protected until menopause, after which their risk increases.

Complications of Untreated Hemochromatosis: The High Cost of Iron Overload

Liver Disease and Cirrhosis

Excessive iron leads to chronic liver damage, ranging from inflammation to cirrhosis, and significantly raises the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer). Liver complications are among the most severe outcomes of untreated hemochromatosis.

Cardiac Problems

Iron deposits in the heart cause cardiomyopathy, weakening the heart muscle and leading to heart failure. Arrhythmias due to iron buildup can also be life-threatening if not managed properly.

Managing Hemochromatosis: Reducing Iron Overload

Phlebotomy (Therapeutic Blood Removal)

Phlebotomy is the cornerstone of treatment for hemochromatosis. By removing one unit of blood (approximately 500 ml) at regular intervals, iron levels can be reduced to safe ranges. The frequency of phlebotomy varies from weekly sessions during the initial reduction phase to maintenance phlebotomies every few months once stable levels are achieved.

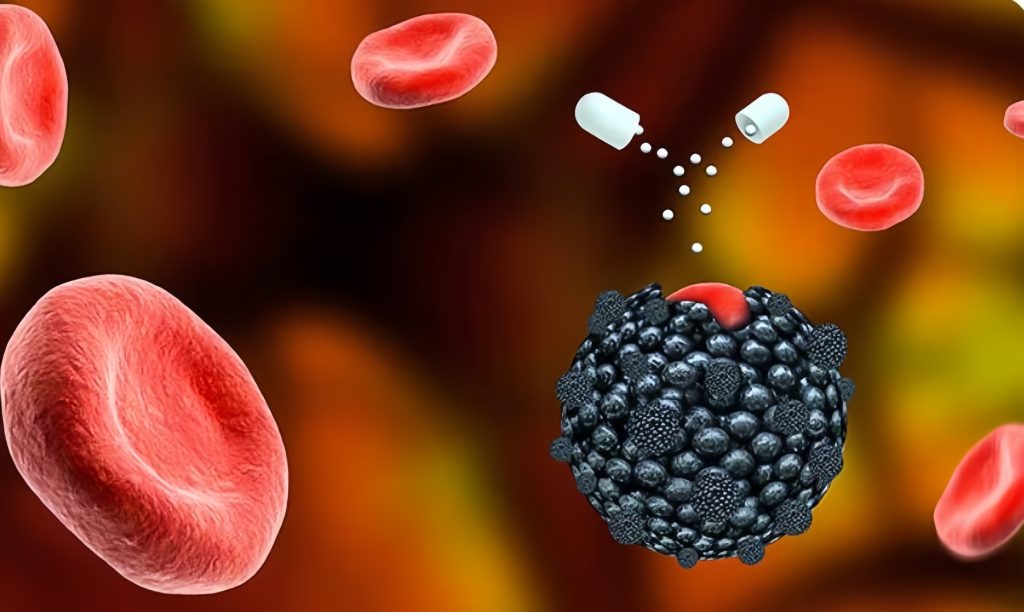

Chelation Therapy

Chelation therapy is an alternative for individuals who cannot undergo phlebotomy, such as those with anemia. Chelation involves medications that bind excess iron, allowing it to be excreted through urine.

Dietary Modifications

Dietary changes are essential in managing iron levels:

- Limit Iron-Rich Foods: Reducing the intake of red meat and avoiding iron-fortified foods help manage iron intake.

- Avoid Vitamin C Supplements: Vitamin C enhances iron absorption, which should be minimized, especially during meals.

- Consume Polyphenol-Rich Beverages: Drinks like tea or coffee contain polyphenols that inhibit iron absorption and can be consumed with meals.

- Avoid Alcohol: Alcohol increases the risk of liver damage, especially when iron levels are high, and should be limited or eliminated.

Lifestyle Adjustments for Managing Hemochromatosis

Regular Monitoring

Frequent blood tests to monitor serum ferritin and transferrin saturation are necessary to ensure iron levels remain in a safe range and to prevent complications.

Family Screening

Genetic counseling and screening are crucial for families with a history of hemochromatosis. Identifying at-risk individuals early enables proactive monitoring and intervention.

Physical Activity

Regular exercise supports cardiovascular health, manages weight, and reduces stress, all of which are beneficial for individuals with hemochromatosis. However, those with severe organ complications should consult a healthcare provider before engaging in strenuous activities.

Conclusion: Living Well with Hemochromatosis

Although hemochromatosis is a challenging condition, it is manageable with early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and lifestyle adjustments. The key to living well with iron overload lies in proactive management—through regular phlebotomy, dietary changes, and ongoing monitoring, individuals with hemochromatosis can effectively control iron levels and prevent complications.

Advances in genetic testing and non-invasive monitoring have made early detection and management of hemochromatosis more accessible than ever. Genetic counseling and regular screenings can make a significant difference for those with a family history, enabling timely intervention to avoid severe organ damage.

With the right care and lifestyle modifications, individuals with hemochromatosis can lead healthy, fulfilling lives. By staying vigilant and adopting a proactive approach, those affected can remain Ironbound—strong and unburdened by the complications of iron overload.